In case you’re not caught up with Frame’s newest weekly series, Thesis Thursday, you can catch up on the last two blog posts here. In a nutshell, this series features installments of my senior thesis written for Rice University’s Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality. It explores the topics of Contact Improvisation, Feminism, feminist performance art, and female empowerment through movement.

Here’s a re-cap of my initial post:

I will argue that CI is a complex feminist practice. The relationship CI has to feminism is complex because it is not inherently feminist, but enables women to have a feminist experience.

If you don’t have time to catch up on the first two posts, have no fear! It’s a perfect week to dive in! This is the first post to go beyond the introductory material and into the “meat” of my first chapter. Enjoy!

——————————–

Chapter One: Influences, Feminist Connections and Contact Improvisation

Part I. Modernist Influences

By Lena Silva

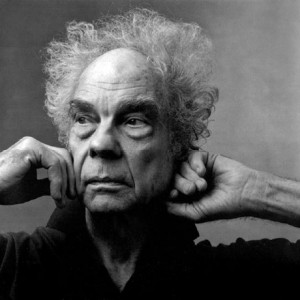

Contact Improvisation, like feminist performance art, has a clear link to modern and postmodern dance as shown through the early career of Steve Paxton. He considered himself an outsider to the dance establishment. Despite having studied gymnastics in his childhood and modern dance at the University of Arizona, Paxton did not believe he was a “real dancer.” Only while dancing for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at age 22 did Paxton begin to identify as a dancer. Paxton admits, “It took me a long time to admit that I was a ‘dancer’…Because I held dancers in such high esteem… it took me a long time to feel I was part of [the New York arts scene]”.[1] Perhaps his affinity with postmodern dance and egalitarian approach to dance making was related to his outsider mentality.

Steve Paxton worked alongside or under many women and men during his formative years as a dancer before CI was initiated. These included Merce Cunningham, José Limón, and Yvonne Rainer. Rainer identified as a feminist performance artist, and Paxton had other colleagues that did so as well. Feminist belonged to the three dance communities that were most influential for Paxton: the Judson Dance Theatre, The Living Theater, and the Grand Union. These individuals and groups provided an influential legacy of egalitarianism and non-hierarchical organization for CI.

Steve Paxton

Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), a major influence on Steve Paxton, was a dancer, choreographer and leader in the American avant-garde for over fifty years, at his most prolific in the 1950’s and 60’s when he worked with Paxton.[2] The most important legacy of Cunningham’s for Paxton was Cunningham’s reliance on collaboration with artists of many different types (including musicians, architects, painter, and actors) and his willingness to experiment. He coined the postmodern technique of chance choreography, which required collaboration John Cage a musician and Cunningham’s life partner. Cage composed musical scores for the dance shows independently of Cunningham’s choreography so that the resulting dance abandoned conventional efforts for dance to match music.

Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), a major influence on Steve Paxton, was a dancer, choreographer and leader in the American avant-garde for over fifty years, at his most prolific in the 1950’s and 60’s when he worked with Paxton.[2] The most important legacy of Cunningham’s for Paxton was Cunningham’s reliance on collaboration with artists of many different types (including musicians, architects, painter, and actors) and his willingness to experiment. He coined the postmodern technique of chance choreography, which required collaboration John Cage a musician and Cunningham’s life partner. Cage composed musical scores for the dance shows independently of Cunningham’s choreography so that the resulting dance abandoned conventional efforts for dance to match music.

Merce Cunningham

However, Paxton’s style of dance making diverged from Cunningham’s insistence on heteronormative partnering. According to Sally Banes, “Cunningham could not, or would not, escape the heritage of classical ballet… men still supported and lifted women…in quite traditional ways. Men did not partner men, nor did women lift or support women.”[3] Paxton and other members of Cunningham’s company questioned the heteronormative conventions, which opened them to a less traditional choreography of gender relations in dance. As early as 1961, while still dancing with Cunningham, Paxton began complicating the gendered nature of choreography in “Proxy,” which the female dancer of the duet lifts the male dancer.[4]

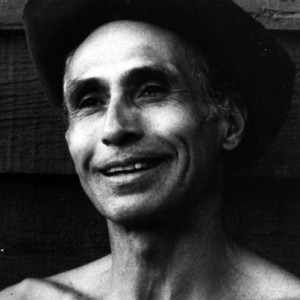

Also during the early 1960’s in New York City, Paxton spent one year dancing with one of the most influential modern dancers in history, José Limón. Limón refused to codify his technique to avoid stifling the creativity of his students. He encouraged them to find their individual expression of a movement, an improvisational element shared by postmodern dance.[5] Limón’s sensitivity toward creative hierarchy was important for Paxton who also chose to set out a minimal frame of reference of movement for dancers rather than impose on them the necessity to dance exactly like him.

Also during the early 1960’s in New York City, Paxton spent one year dancing with one of the most influential modern dancers in history, José Limón. Limón refused to codify his technique to avoid stifling the creativity of his students. He encouraged them to find their individual expression of a movement, an improvisational element shared by postmodern dance.[5] Limón’s sensitivity toward creative hierarchy was important for Paxton who also chose to set out a minimal frame of reference of movement for dancers rather than impose on them the necessity to dance exactly like him.

Jose Limon

Limón appointed Doris Humphrey to be the artistic director of his company rather than personally assuming the position. That he chose a woman is notable. Despite the prestige some women had in the modern dance world, such as Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham, many others struggled to attain prominence at the level of their male contemporaries. Humphrey is acclaimed for opening up modern dance to the nuances of gravity with her principle of “fall and recovery,” which focuses on organic falls and rebounds of the body that arise from shifts in weight.[6] Humphrey said gravity was “…the very core of all movement, in my opinion.”[7] Her style is similar to what became central to CI movement technique: focusing on gravity and sharing changes in weight between partners as impetus for spontaneous movement.

Limón appointed Doris Humphrey to be the artistic director of his company rather than personally assuming the position. That he chose a woman is notable. Despite the prestige some women had in the modern dance world, such as Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham, many others struggled to attain prominence at the level of their male contemporaries. Humphrey is acclaimed for opening up modern dance to the nuances of gravity with her principle of “fall and recovery,” which focuses on organic falls and rebounds of the body that arise from shifts in weight.[6] Humphrey said gravity was “…the very core of all movement, in my opinion.”[7] Her style is similar to what became central to CI movement technique: focusing on gravity and sharing changes in weight between partners as impetus for spontaneous movement.

Dorris Humphrey

[1] Steve Paxton, “How Important is Dance? I Think it May be Critical!” The Wise Body: Conversations with Experienced Dancers, ed. Jacky Lansley and Fergus Early (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 89.

[2] Sally R. Banes, “Feminism and American Postmodern Dance,” Ballett [sic] International, no. 6 (1996): 34-41.

[3] Ibid., 35.

[4] Banes, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theatre, 1962-1964, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 58-60.

[5] June Dunbar, Jose Limón: The Artist Re-Viewed (New York: Routledge, 2000), 38 and 113.

[6] Lesley Main, Directing the Dance Legacy of Doris Humphrey, (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), 16-17.

[7] Ibid., 17.

————————————

Stay tuned for the next installment of my thesis that will focus on the postmodern influences on CI!

My partner and I performing a CI duet for Rice Dance Theatre’s Fall 2012 show.